While the tresoor is nearly finished; all woodwork has been done and it is awaiting the hinges and lock, the blog is somewhat lagging behind with the story on how it was made. In this post I want to focus on the large side panels. The four large side panels were planned as gothic tracery work - but blinded, not open as in the scapradekijn for Amsterdam Castle (Muiderslot). Previous posts on the tresoor for Castle Hernen can be found here (Part 1) and here (Part 2).

<

An Austrian armoire with circular patterns on the doors as well as on the feet and crown of the armoire. Originally from around Salzburg, now in Schloss Seebarn near Wien, Austria. Made from stone pine and limewood. 261.5 x 192 x 50 cm. Dated second half of the 15th century. Photo scanned from Franz Windisch-Graetz - Möbel Europas band 1 - Romanik - Gotik.

I you look at single late medieval furniture pieces containing tracery panels, most of them have tracery panels that within each furniture item are slightly different. The basic pattern is the same, but the details vary. For example, one panel may contain four roundels, while the panel next to it contains six. I intended to do the same with the four large panels for the sides of the tresoor.

I created a basic template for the panel in which the large round 'window' would contain a different pattern for each panel. Furthermore, two versions of the lower part of the template were designed, one containing a four-leaved flower (rosette), the other pointed tracery elements.

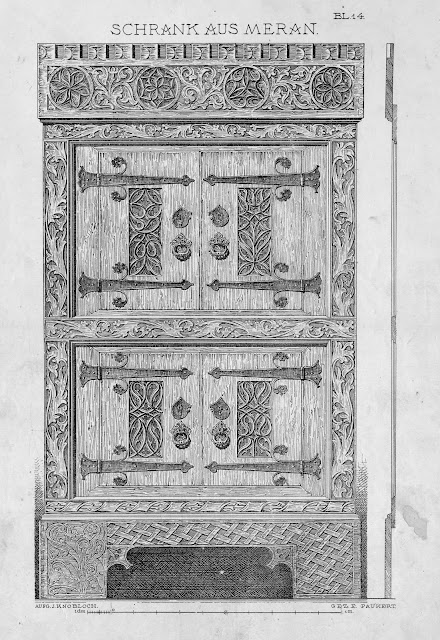

For the round designed I looked at historical patterns and decided to use those found on a 15th century chest in the Danish historic museum. Similar designs could be found on an late medieval armoire from Austria (and multiple others). To find the thickness of the panels, and the depth of the tracery, I used the few medieval panels that I own. Note that the panel thickness of the (square) tresoor of castle Muiderslot was about twice the thickness of my own panels. As both thicknesses are historically correct, it became mostly an economic decision for me - thinner panels being cheaper, aside from being easier to handle.

Sketching the tracery designs on 5 mm grid paper (i.e. full size). The (top) red part of the design was later cut out with a scissor and used as a drawing template for the first layer on the oak panel.

The oaken boards I used were quarter sawn, with an even grain pattern and thinned to 2 cm. The panels were 23 cm wide and much longer than the 43 cm needed. The surplus material was used for the carving smaller (middle) side panels, while they were still attached to the large panel.

(Left) Both my original medieval panel and the panel for the tresoor have the same 2 cm thickness. (Right) Inside the dressoir at Muiderslot, showing a thickness of around 4 cm.

There are two (historic) ways producing blinded tracery panels: (1) making an openwork tracery panel and then blinding it by glueing another thin board at the back; and (2) carving it from one piece of wood. The first method has the advantage that you can use saws and files, as well as work from both sides. The disadvantage is that the panel becomes very thin at the deepest layers and prone to breaking. I used the second method.

The six-sided dressoir at Chateau Langeais, France showing a damaged tracery panel. That the tracery panel consist of 2 glued boards can easily seen by the undamaged underlying 'blinding' panel.

Both methods historically involve removing a lot of material by hand (chisel or perhaps a router plane. Luckily, we now have the electric hand-router at our disposal to help with that, although the machine needs some modifications before it can be used. The resting platform of a hand router is small. Too small for freehand routing to be of use in making tracery panels, so it needed to be enlarged. The router platform had to be more than twice the width of the panel, in order to have support from it sides. I did use 9 mm multiplex board to create the platform, and used the same cut-out /screw-hole pattern as the original resting platform.

The router was used freehand till a distance of 1-2 mm of the drawn pattern line, and then cleaned to the drawing line with carving knife, chisels and gouges. A 45 degree chamfer was cut along the edges. When one layer was ready, the patterns of the next, deeper layer was drawn and the process repeated with the router set at a larger depth. Using this method, making the tracery patterns was really fast and easy, and proved even quicker than making the linenfold panels. The following photoset shows the different stages in creating the tracery panels.

(Left) Layer 3 circular window, drawing pattern has been added. (Middle) Layer 3, circular window, showing the small decoration on top of the circle. (Right) Drawing of a circular window of another panel.

(Left) Layer 2 circular window, routed but not yet cleaned. (Middle) Layer 3 circular window, everything is routed and in the process of being cleaned. (Right) Layer 3 circular window, drawing pattern, the central rosette is finished.

(Left) Layer 2 bottom, drawing added. (Middle) Layer 2 bottom, after routing and cleaning; the large chamfer from layer 0 to layer 2 at the bottom has been made. (Right) Layer 3 bottom, drawing pattern for the non-rosette pencil windows has been added.

(Left) Layer 3 bottom, all routed, but only the bottom part is cleaned. (Middle) Layer 3 under, the lower part is routed and cleaned, the top part contains the drawing with the rosettes. (Right) Layer 2 bottom, the pencil windows are being cleaned; the large chamfer at the bottom has already been made.

(Left) Layer 2 top, routed and cleaned; the cuts at the top of the ‘pencils’ have not yet been done. (Middle) Layer 2 top, routed and cleaned; here, the cuts at the top of the ‘pencils’ have been added.(Right) Layer 2 top, the line on the left side of the panel shows the place where the ‘bottleneck’ of the third layer will be placed in the thin windows.

(Left) Layer 2 top, routed and cleaned; the cuts at the top of the ‘pencils’ will be done after layer 3 as they are relatively fragile. (Right) Layer 3 top, the finished pattern.

(Left) Detail of the rosettes at the bottom of a panel. (Right) Process of carving a triangular hole with a knob (originally I planned a rosette, but changed it as there would be too much rosettes on this part of the panel).

The rosettes were made by hand using different sizes of gouges. Any knobs in the design were rounded using a small chisel along the grain, and sanding it smooth using a piece of 180 grid sandpaper. The triangular deep spots were made using a straight fishtailed gouge (F1). The tracery panels were finished by removing the plunge marks of the

router bit on the bottom layers with a chisel, and adding special

accents with a carving knife where necessary.

All four tracery panels with their carving finished. On top you can already see the designs drawn for the smaller middle panels.

All four tracery panels with their carving finished. On top you can already see the designs drawn for the smaller middle panels.

The panels were then sawn to their correct height. The backside of the panels were chamfered using a 2 inch round moulding plane in order to fit in the grooves of the tresoor frame. Finally, the panels were oiled with linseed oil. The oil on the tracery pattern was applied with a brush in order reach the deepest parts that could not be reached by a cloth with oil.