It all began when we found a book on excavations in Arnemuiden, the town Anne was born. Among the finds at the harbours edge was a curious red earthenware pot, dating from the late middle ages. A similar pot had been found in the nearby city of Middelburg. As this type of pot was only found in Zeeland, a delta province with (during medieval times) lots of small islands and fisher-folk, and plenty of opportunity to gather (free) mussels around the shore, it was thought to be a pan used to cook mussels. As we happen to like cooked mussels, and this was a medieval pot from Anne's home town, we wanted to add a replica of this mussel pot to our cooking inventory. We looked if there was a potter that was willing to make the replica and ended up at

Atelier Jera, run by Elly van Leeuwen from Leiden, the Netherlands.

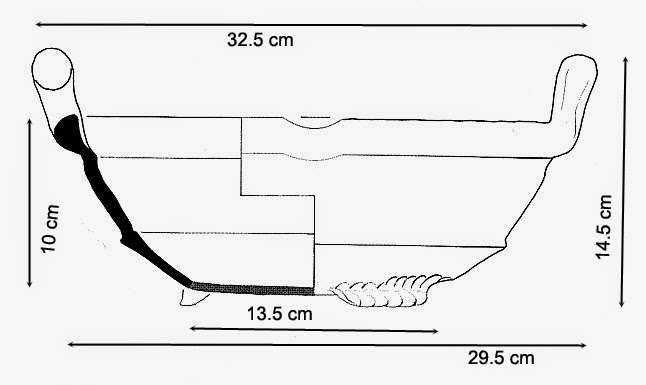

A red earthenware 'mussels bowl' with lead-glazing inside standing on three rims. Dated around 1375-1450.

Middelburg, Berghuijskazerne, now in the Zeeuws Museum, Middelburg, the Netherlands.

The red earthenware 'mussels bowl' with lead glazing found in Arnemuiden, the Netherlands.

Dated around 1350-1450. The sizes are recalculated based on maximum diameter provided.

She made a very beautifully crafted replica of the mussels bowl, as well as a replacement for our

jack-dawed milk bowl. Her bowl is slightly smaller, 28 cm diameter and 11 cm high. We tested our new mussels pot on our next event in Eindhoven. Of course using a medieval recipe for mussels. Below we provide the recipes for three different medieval dishes containing mussels.

Our mussels bowl replica made by Elly van Leeuwen.

You might wonder how mussels gathered around the shore would end up fresh in the mainland (e.g. around the Historic Open Air Museum in Eindhoven). There is some evidence that mussels were transported during medieval times in barrels filled with salt water. This prevented them from being spoiled.

Last weekend in the Historic Open Air Museum in Eindhoven we tried two of the three medieval mussels recipes that are provided below.

Cawdel of Muskels

This is an interesting recipe for mussels and leeks in almond milk, from 'the Forme of Cury' an English cookbook from the 14th century (recipe 127). The modern adaptation is from 'Pleyn delit' by Constance B. Hieatt, Brenda Hosington and Sharon Butler (ISBN 0-8020-7632-7).

Cawdel of muskels, a tasty soup-like recipe.

Take and seep muskels; pyke hem clene, and waisshe hem clene in wyne. Take almaundes & bray hem. Take somma of the muskels and grynde hem, & some hewe smale; drawe the muskels yground with the self broth. Wryng the almaundes with faire water. Do alle thise togider; do therto verjous and vyneger. Take whyte of lekes & perboile hem wel; wryng oute the water and hewe hem smale. Cast oile therto, with oynouns perboiled & mynced smale; do therto powder fort, saffroun & salt a lytel. Seep it, not to stondyng, & messe it forth.

Add salt and saffron and boil the mussels. They are ready when they are open.

- 1/2 cup of ground almonds

- 1/2 cup of water

- 1-1.5 kg mussels in shell

- 2 medium onions, peeled and quartered

- 3-4 leeks, washed and thinly sliced

- 1 bottle of dry white wine

- 2 tablespoons white wine vinegar

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon saffron

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 1/4 teaspoon each ground ginger, all spice, and pepper.

Take the mussels out of their shell and chop them to pieces.

Draw thick almond milk from the ground almonds and water. Soak mussels

in cold water and discard those that open prematurely. Put them in a

large pot with leeks, onions, wine, vinegar, salt and saffron. Bring to a

boil, then turn the heat down and simmer until the shells open (about 5

minutes). Stain broth through a cheesecloth and reserve. shell mussels

and discard the shells. Chop onions and leeks and sauté them them gently

in oil for a few minutes. Meanwhile grind (blend) half the cooked

mussels with a small amount of the broth. Chop the remaining mussels

more coarsely with a knife. Combine all of these ingredients with the

almond milk, adding broth if more liquid seems needed. Simmer gently to

reheat, stirring constantly; do not overcook. Season to taste.

Saute the onions and leeks.

Mussels in the shell

The following is a recipe for cooked mussels from Manuscript M.S. B.L.

Harleian H4016, recipe 106 of around 1450. Taken from the book 'The

culinary recipes of medieval England' by Constance B. Hieatt (ISBN

978-1-909248-30-4).

Take and pick over good mussels and put them in a pot;

add them to minced onions and a good quantity of pepper and wine, and a little vinegar.

As soon as they begin to gape, take them from the fire, and serve hot in a dish with the same broth.

The mussels in the shell were made using the new mussels bowl.

This recipe is, in fact, much alike the modern cooked mussels. Mussels are boiled in white wine, together with a drop of vinegar, some vegetables (for example onions) and spices (pepper). When the shell is open they are ready to eat. You can use an empty open shell as pincers to pry another mussel out of its shell. The use of vinegar and pepper gives it a interesting twist from the modern cooked mussels.

'Ein hofelich spise von Ostren' (jugged mussels)

This mussels recipe stems from medieval France and was taken from the German book 'Wie man eyn teutsches Mannsbild bey Kräfften hält' by H.J. Fahrenkamp (ISBN 3-89996-264-8). The recipes in this book seem genuine, but the author is lax in providing the exact sources.

- 1.5 kg mussels

- 3-4 tablespoons oil

- 1 medium sized onion

- 100 g breadcrumbs

- 1/2 l dry white wine

- 1-2 tablespoons wine vinegar

- some bay leaf, parsley and tarragon

- 1/2 teaspoon ginger

- 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

- a bit of saffron

- white pepper, salt

Wash the mussels and throw away the ones with an open shell. Put the rest in a large pan with some oil and heat strongly for around 5 minutes, while shaking the pan, until the shell have opened. Throw away the unopened ones. Take the pan from the fire and put through a sieve, catching the mussel-oil liquid in a bowl. Take the muscles from the shell and set aside. Cut the onion in fine pieces and stir fry them in a little oil. Add the breadcrumbs and stir. Add the wine and vinegar and the herbs and let it simmer for 10 minutes. Remove the herbs and use a mixer to make a smooth purée. If necessary add the mussel-oil liquid. Add the spices, keeping in mind that none should give a dominant flavour. Add the mussels to the sauce and reheat the mixture slowly.

Medieval mussels with St. Ambrose in the Book of Hours

of Catherina of Cleves, by the Utrecht Master of Catherina of Cleves,

Ms. M. 917, page 244. Note that the crab has too many legs.