The Sedia Savonarola is a late medieval folding chair that originated in Northern Italy and became popular during the 15th and 16th century. Most extant examples date from this period and were made in Italy and the Alpine region. Though the basics of this chair type are simple, there is a lot of variation in armrest, backrest and feet models, as well as the type of wood used. Usually the chair has eight rows of S-curved legs at each side.

The chair type had a revival in the 20th century, and was factory produced, having iron pins for folding and an elaborately carved back.

The chair type had a revival in the 20th century, and was factory produced, having iron pins for folding and an elaborately carved back.

A pictorial diversity of Savonarola chairs

The 15th century Maximilian Room in Schloss Tratzberg, Jenberg, Austria. The three Savonarola chairs show the variety in height, backrest and number of legs. The one left in the back has 10 legs on each side.

Three 15th century Savonarola chairs in Leeds Castle, Maidstone, UK. The one in front is inlaid with ivory or bone. All chairs are made in Italy and from walnut. Image from the Leeds Castle guidebook.

Two Savonarola chairs from the Museum fur Angewandte Kunst, Koln, Germany.. Left: walnut, height 86 cm, width 96 cm, depth 59 cm. Seating height 52.5 cm. North Italy, 2nd half 15th century. Right: walnut, with oak feet rail and apple backrest. Height 84 cm, width 68 cm, depth 52 cm, seating height 50 cm. Switzerland, mid 15th century. The front part of the seating is larger and covers the triangle between the joints. More colour photos of this chair are found in another post Medieval furniture from Koln. Images from museum catalogue MAK Koln.

This chair is from the formerly collection of Dr. Albert Figdor. Walnut, Tirol 1500. height 90 cm, width 68 cm. The armrest has a movable ring at the front end. The foot rail has claws and stands at an angle. Image from the 1930 auction catalogue.

The left chair is also from the collection of Dr. Albert Figdor. Walnut, Southern Alps, 15th century. height 88 cm, width 59 cm. The front is decorated with woodcarvings. The backrest has some carved lines. Image from the 1930 auction catalogue. Right: Chair from the Museum fur Kunsthandwerk, Frankfurt.. Made of walnut, oak and beech. 16th century. Image from internet

Two chairs presumably from the Museo San Marco in Florence dating from the 15-16th century. The left chair has renaissance carvings at the backrest. Both chairs have carvings at the front legs. Images from internet.

The chair on the left is also from the Museo San Marco in Florence. 15th century. The chair on the right is from Lombardy. 1500. It is heavily inlaid with ivory or bone, the most likely wood used is walnut. Also here the feet rail stands at and angle. The chair has an exceptionally wide seating. Images from internet.

Right: Walnut chair from Tuscany, Italy, mid 16th century. Height 96 cm, width 74 cm, depth 58 cm.

Burg Kreuzenstern, Vienna. Left: Italy, 2nd half of the 16th century. Walnut, height 98 cm, width 66, width 47 cm. The armrest has deepened rosettes. The backrest falls within the armrest. Landesmuseum, Graz, Austria. Images from Mobel Europas 2: Renaissance - Manierismus by Windisch-Graetz..

Left: 15th century chair from Tirol, Austria. Beech with pine backrest. Backrest with openwork Gothic carving. Height 92 cm, width 59 cm, depth 42 cm. Burg Kreuzenstern, Vienna, Austria. Image from Mobel Europas 1: Romanik - Gotik by Windisch-Graetz. Right: Chair, North Italy, first half 16th century. Museo Nazionale Bargello, Florence, Italy. Image from Oude Meubels by S. Muller-Christemsem..

Left: Chair with a peculiar form of backrest. 16th century. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munchen. Right: An unidentified savonarola chair. Images from internet.

Folding chair without a backrest and with 12 legs at each side. Beech, end of 15th century Image from Le Mobilier Francais du Moyen Age a la Renaissance by J. Boccador.

Two savonarola chairs from Italy or southern France. Height 94 cm, width

61 cm and depth 51 and 56 cm. Walnut, mid 16th century. Image from Le

Mobilier Francais du Moyen Age a la Renaissance by J. Boccador.

Two chairs from Hampel Fine Art auction house, Munchen, Germany. Such antique chairs will cost between 2,500-5,000 Euro. Left: Walnut, height: 86 cm, width: 63 cm, depth: 49 cm. Early 17th century. Right: Beech, 80 cm high, Lombardy, 16th century.

A modern Savonarola chair from the 20th century. These chairs can be bought cheaply at internet (e.g. ebay Italy) for 15-90 Euro. This particular one was borrowed from a friend to have some idea of the dimensions and seating quality. This one is quite frail compared to my oak chair.. The joints are connected by iron dowels screwed with iron nuts.

Construction of the Savonarola chair

My Savonarola chair was constructed several years ago in 2004. I did not take that many photos then, so there are only a few photos of the chair during construction. I still have some spare parts of the chair, as well as some of the jigs in my workshop, so I have added some 'recent' photos of them as well. Basically the plan for making the Savonarola chair is that of Charles Oakley's Peacock folding chair. He has provided clear and accurate instructions for a medieval replica using modern tools. I have only changed some dimensions of the chair - mine has a higher seating, due to an increased length of the legs. This makes the seating height of my chair uncomfortable for most people. Also different is how the feet rail, arm rest and backrest look, however the mode of construction is the same. As already shown above in the pictorial variety of the chairs, they can look different.

My Savonarola chair, European oak, finished with furniture soap. Nowadays it has a linseed finish.

I used European oak (Quercus robur) for the chair. Boards of 23 mm thick for the legs and seating parts and 18 mm for the backrest. Thicker pieces (40 mm) were used for the feet and armrest. The legs were roughly sawn with a band-saw, and then made exactly identical using a router and mdf jig. This is very important as the folding joints will not work when they are different. I drilled the holes for the joints first, so I could also used them to fix the leg with bolts to the jig at the same position. All the 16 (well actually 18, I had two spare ones) identical legs were also rounded using an ogee cutter with the router (table).

Two routing jigs are needed for the legs, one for each side. The leg is fixed in the middle by two bolts, and at both ends with toggle clamps screwed to the jig (now removed). In the middle a mdf model leg is shown, used for drawing the legs on the oak boards.

The block where the toggle clamp was fixed has some space allowance for the unrouted part of the leg. Right: The type of router cutter used with a top cutter and a guidance ring beneath it.

A tenon at both ends of the leg was shaped as follows: the two flat parts of an end were cut with a spindle moulder (or shaper). Another jig (no photo) was used to hold the leg at an identical position, again making use of the joint holes and bolts. The two curved parts of an end were sawn by hand.

The seating parts (also 16 with 2 spare parts) are rectangular and were the easiest part to make. the 45 degree angle at each end was cut with a circular saw set at a fixed length. The length of the seating parts were also rounded using an ogee cutter with a router (table).

The seating parts (also 16 with 2 spare parts) are rectangular and were the easiest part to make. the 45 degree angle at each end was cut with a circular saw set at a fixed length. The length of the seating parts were also rounded using an ogee cutter with a router (table).

The two spare legs and seating parts with the mdf leg model. The angle of the seating parts is 45 degrees.

The backrest, feet rails and armrest were sawn with a band-saw or hand-held power jig saw and finished with spoke shave, gouges and belt sander. To make the mortises for the leg tenons, holes were drilled with a hand drill at the appropriate places, which were further cut out square by hand with chisels. The exact places for the mortise was determined by building the legs and seating with the dowel joint for the rod and placing them on the leg rails. Each leg was numbered to ensure the same place during final construction. Note that there should be some space allowance (between 0.5 and 1 mm) between the legs, to allow easy folding of the chair.

The tenons at the arm rest side. Each is numbered for and exact fit with the mortise..

The mortises of the arm rest and the slot for the backrest.

Cutting the groove for the backrest in the armrest was done by hand, using a clamped block to guide the saw. A router plane was used to clear out the groove. At the other side of the armrest decorative rosettes were carved. Each rosette has 10 leaves.

Detail of the groove of the backrest. The groove is 1 cm deep at each side of the armrest.

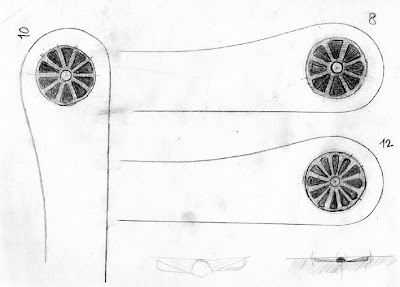

Some tests on the number (8, 10 or 12) of leaves for the rosettes on armrest. The ten leaves version was used.

The caps for the (joint) dowels were drilled using a dowel cutter to produce 20 mm diameter oak dowels, drilling a 12 mm hole in it with a Forstner drill bit (with a drill press). Then I put a small piece of Duct tape on a 12 mm dowel rod and added the cap onto it. This way it was fixed relatively stable to the dowel rod. The cap now could be easily and safely be rounded with a large belt sander, using the dowel rod as a handle. By rotating the dowel rod constantly a nice dome-formed cap was created. The cap was carefully glued to the dowel of the joint - spilled glue would glue the joint and spoil the folding of the chair.

The rounded cap; 8 are needed for a chair.

Some spare oak 20 mm dowels, the 12 mm dowel with tape on the ends to be used as a handle

and a (smaller) pine model giving an idea how the cap is fixed to the dowel handle.

The glue for the caps is the only glue used in making this chair. The mortise and tenons were not glued at all. They have been stable for more than 7 years of continuous use, and only now are beginning to wriggle a bit loose. The correct solution will be to add two dowel pins at each armrest and leg rail at the position of front and back leg to fix them permanently.

The loose pieces of the chair were finished at that time (2005) with soap. Furniture soap consists of white soap flakes that make a thick creamy 'soap paint' with a little water added. When dried it has a hard protective layer, which makes the wood look a bit bleached. A few layers of soap were added. It is of course not watertight, but stains are cleaned easily with a little water and soap. After all parts of the chair were treated with soap, the chair was put together. Because our other medieval furniture has (later) been finished with linseed oil, I have removed the soap coating with water in 2011 with a lot of water under the shower, and replaced it (after drying) with linseed oil.

The two backrests with linseed oil finishing. The top one is my favourite.

The round of the bottom one was supposed to have a heraldic sign.

The round of the bottom one was supposed to have a heraldic sign.

I made a second, differently formed backrest with the idea of carving a heraldic sign in the central round. It never happened, as I liked the other backrest more.

The Savonarola chair in a folded state. here it still has the soap finish.

Measurements

Below are the measurements of the chair. The legs are 23 mm thick and around 30 mm wide, the seating parts 23 mm by 27 mm thick.

A third alternative backrest.