Already some large medieval saws have been discussed in the medieval toolchest. This post features another large saw that does not fit in the chest: the pit-saw. Actually the English name is a bit misleading, as no 'pit' is involved in the sawing process; the names for this saw in other languages are more appropriate, such as the Dutch 'raamzaag' or German 'Rahmensäge' (window-saw) or French scieage de long (long saw). Basically, the saw consists of a rectangular frame with a saw-blade attached in the middle.

Already some large medieval saws have been discussed in the medieval toolchest. This post features another large saw that does not fit in the chest: the pit-saw. Actually the English name is a bit misleading, as no 'pit' is involved in the sawing process; the names for this saw in other languages are more appropriate, such as the Dutch 'raamzaag' or German 'Rahmensäge' (window-saw) or French scieage de long (long saw). Basically, the saw consists of a rectangular frame with a saw-blade attached in the middle.

Heintz Seger († before 1423). Folio 39 recto, Hausbücher der Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderhausstiftung, Nurnberg, Germany.

The saw was already in use in Roman times, as evidenced by several mosaics and mural sculptures from that period. During the medieval time period the saw was ubiquitously in use, although wooden planks were also produced by (German) sawmills and exported to neighbouring countries. This saw continued to be in use until last century. I have spoken with someone who used to saw planks from tree logs at his fathers workshop on a sawing scaffold.

A Roman mural sculpture of a woodworkers shop showing a small pitsaw on the left. 1st century AD, Capitoline Museum (Montemartini), Rome, Italy.

Two men were necessary to work the saw on a scaffold. Here, a distinction between Southern and Northern Europe is found: Northern Europe worked with a log resting on two high scaffolds (see the images from the Mendelschen Hausbücher), while Italy for instance used a low single scaffold with the log resting on side on the ground and the other protruding in the air (e.g. the mosaic from the San Marco in Venice or the fresco in the Camposanto in Pisa, both Italy). The last method was also used in China in the early 20th century to saw a log.

Two more sawyers from the Hausbuch of the Mendelschen Zwölfbrüderhausstiftung using a pit-saw. It may seem as if the saw is used by one person only, but one has to keep in mind that Hausbuch contained the picture of the retired brother in his craft, i.e. one person. The saws do show handles at both ends. Left: Cuncz Prendel

(† 1443),

Folio 65 verso; Right: Hans († before 1414), Folio 1 recto.

Left: Building Noah's ark, mosaic in the San Marco Basilica, Venice, Italy. Right: Mural painting from the Cathedral de Teruel, Spain, XIIIe century.

The main function of the long pitsaw was to cut planks length-wise from a log. The man on top of the scaffold pulled the saw upwards (the handle on top of the saw was to make this easier for him), while the man on the ground performed the sawing action. To make a long sawing stroke, the handle for him was placed at an 90 degree angle from the sawing frame. In the medieval and renaissance period specialised sawing guilds appeared, for instance in Belgium.

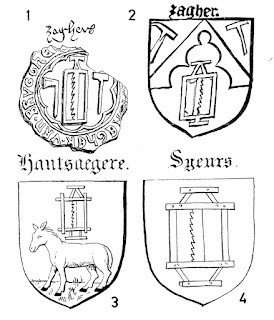

(1) Belgian sawing guild seal from Bruges (14th century); (2) heraldic sign of the sawing guild in Ghent (16th century), (3) Brussels (16th century) and (4) Liège (16th century). Image scanned from 'Op en om de middeleeuwse bouwplaats' by Frieda van Tychem.

However, also smaller versions of this saw existed that can also be used by one man. Recently, these small saws are becoming popular again. They are now known as the 'Roubo saw', after an engraving of this saw in the 18th century book 'L'art du menusier' by André-Jacob Roubo. The engraving shows the saw in use to cut thin planks for use as veneer, although two men are used here. Roubo also showed the working of the large pit-saw, this engraving is not often shown.

The Roubo veneer saw, shown in a (commonly found) engraving in Lárt du menusier.

The Roubo pit-saw, shown in an engraving in Lárt du menusier.

A smaller Roubo veneer saw used by two men, shown in an engraving in Lárt du menusier.

Constructing a small 'Roubo' saw

Our 'Roubo' saw made from oak and fitted with a Japanese saw blade.

For our project to make a six-sided buffet for Castle Hernen we needed

to saw a 1.5 metre beam lengthwise at some angles that were not

possible using an electric sawing machine. One of the alternative options was to

use a Roubo type saw. However, we had to construct such a saw first. The

construction scheme as well as all the necessary metal parts can easily

be obtained from internet (e.g. from Blackburn tools), as well as instructional videos (here and here).

However, the metal parts for the tool are very expensive and likely the costs of

transport to Europe and customs taxes would double the cost. This was

not an attractive option for us. Therefore, we chose the cheap option:

an 70 cm long Japanese frame saw blade was purchased from Dictum Tools

at a fraction of cost for a Blackburn blade. Furthermore, the necessary steel brackets

were bought from a local internet blacksmith. We only needed brackets

that were 5 cm wide, but the blacksmith only sold them at 2 metres

length! Luckily, he offered two free cuts in the steel - so, we received

our 5 cm brackets, as well as 1.9 metres 'waste' for only 15 euro (ex

transport cost).

Left: the 5 x 8 x 3 cm steel bracket. A kerf was made in the middle to hold the sawblade. Right: the brass V-shaped rod to secure the sawblade in the bracket. The sawblade itself has a width of 4 cm.

The Japanese saw blade.

For the wooden frame we used oak, as that was readily available in the

appropriate lengths. The handles were formed with help of a bandsaw,

spokeshave, chisel and files. The four wooden parts of frame are just

connected with mortise and tenons without any pins or glue. The tension

of the saw blade is enough to to pull the parts strongly together. The Roubo is 27 cm thick, has a length off 82 cm and a width (max at the handle) 83 cm. The space between the wooden stiles (i.e. the max width of the item to saw) is 41 cm.

Left: The length of the frame stiles is crucial. They should be long enough to be able to provide the tension for the saw blade This photo shows the testing of the correct length. Right: The frame was clamped tightly before the wedges were added.

A double wedge is used to ensure that the bracket stays in a 90 degree position.

A kerf needed to be made in each bracket to hold the ends of the sawblade. A small hacksaw was used for this, but the kerf needed to be widened with help of a thin cutting wheel on a Dremel. A 4 mm V-shaped brass rod was used to secure the saw blade in the bracket. At one end of a bracket a thin wedge was inserted to create tension on the sawblade, and add to the rigidity of the frame. Finally, the wooden frame was covered with a layer of linseed oil.

Our Roubo saw at work on the buffet for castle Hernen.

The space for the sawing action is limited in the workshop, resulting in the drop of some other tools from the wall ...

The space for the sawing action is limited in the workshop, resulting in the drop of some other tools from the wall ...

Sources:

- F. van Tychem. 1966. Op en om de middeleeuwse bouwplaats. Verhandelingen van de koninklijke Vlaamse academie voor wetenschappen, letteren en schone kunsten van België, jaargang XXVIII no. 19.

- H.T. Schadwinkel and G. Heine. 1999. Das Werkzeug des Zimmermanns. Verlag Th. Schäfer, Hannover, Germany.

- W.L. Goodman. 1964. The history of woodworking tools. Bell and Hyman Ltd. London, UK.