|

| The hallway on the first floor of Kloster Isenhagen. |

In this last post on the medieval furniture of the convent Isenhagen at the Luneburger moor, the chests are shown. All the medieval chests of the

Luneburger convents (in particulary Wienhausen and Ebstorf, but also Lune, Medingen and Isenhagen as well as those in other musea) including the ones shown in this post, are

described in detail in the books

Die gotischen Truhen der Luneburger Heidekloster by K.H. Stulpnagel and

Truhen, Kisten, Laden vom Mittelalter bis zum gegenwart am beispiel der Luneburger Heide by T. Albrecht. These books also contain every detail on the construction. Most of these chests are from the 13th to 15th century, and are of the hutch-type. But there are some specific differences in construction of the chests of this area that enables them to be ordered into four subtypes: the Celler type, the Braunschweiger type, the Luneburger type and the Hannover type. All types have some common characteristics. They slightly converge to the top, the boards more than the legs. The boards of the bottom of the chest are connected by tongue and groove, and with a groove to the side boards and legs. Most chests have small side-chests inside on the left or right side. Also a small ridge can be found near the top of the chest on which small items could be placed.

The Celler type has sturdy legs, the boards at the front are connected with each other with dowels, and with a haunched tenon to the legs. The lower part of the legs can be decorated with simple chipcarving or zig-zag patterns. The lid of the chest is slightly rounded and hinges on a wooden dowel or thorn at the side. Finally, the wooden nails securing the tenons are placed at specific positions. The lock is consist usually of an iron bar at the inside. Chests of the Celler type are the earliest to appear but are not found after 1400.

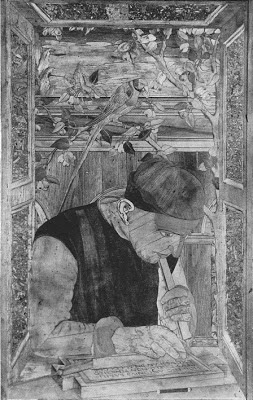

An "explosion" drawing of a chest of the Celler type around 1300. You can see that the board converge to the top and that the lid is slightlly rounded. Image by K.H. Stulpnagel from the book Die gotischen Truhen der Luneburger Heidekloster.

The Branschweiger type shares many characteristics of the Celler type. The lid and lock for instance are of the same type. The boards are jointed with dowels or just butted. The connection of the boards to the legs can be either a simple tenon, or a haunched tenon. The lower middle boards often extend to the bottom of the legs and are usually decorated. Also the Braunschweiger type is only produced until 1400.

The Luneburger chest type has a flat lid, which is connected to the back of the chest with ring hinges. Sometime this chest type is found with a framework to the sides. These chests are also wider and measure over 1.25 m, making them appear leaner. The middle boards are connected to each other with dowels, and to the legs with simple tenons or a haunched tenon. The Luneburger type is produced onwards till the 16th century.

An "explosion" drawing of a Luneburger type chest. At the back and right side the top ridge is shown. The lid is decorated and connects to the chest with a ring hinge. Image by K.H. Stulpnagel from the book Die gotischen Truhen der Luneburger Heidekloster.

The last type, the Hannover chest type can be distinguished on the connection of the sides to the legs and the specific positions of the nails. There are no Hannover type chests in Kloster Isenhagen. All the chests from the Luneburger convents could be dated dendrochronologically.

Characteristics of other, non-Luneburger medieval hutch type chests are that they do not converge. Most often they have strap hinges and iron bands as decoration. Also the bottom boards are commonly nailed.

Chest TR-NR 220 (ISN Ba 84) . Made of oak and dated around 1310. Height 91 cm, width 113 cm, depth 70 cm. Decorated with hardly visible cross decorations. Celler construction type. On the inside of the chest is a small side chest.

Chest TR-NR 409 (ISN Ba 83). Made of oak, dated 1375 and of Braunschweiger construction. Height 69 cm, width 85 cm, depth 53.7 cm. The chest is decorated with iron nails. On the left inside there is a small side chest. More details of this chest are shown in a previous post 'unconventional photography'.

Chest TR-NR 409 (ISN Ba 83). Made of oak, dated 1375 and of Braunschweiger construction. Height 69 cm, width 85 cm, depth 53.7 cm. The chest is decorated with iron nails. On the left inside there is a small side chest. More details of this chest are shown in a previous post 'unconventional photography'.

Left photo: Chest TR-NR 410 (ISN Ba 87) is also made of oak and dated around 1379. Height 94.5 cm, width 161.5 cm, depth 77.3 cm. The chest is of the Braunschweiger construction, though this is not visible on this photo. On the right inside there is a small side chest, on the left inside a high ridge on which items can be laid. The chest has no specific decoration.

Chest TR-NR 325 (ISN Ba 85) (Right photo top and photo below) is made of oak and dated between 1500-1550. It is the very large (and heavy - around 200 kg) travelling chest of the abbess Margarete von Boldensen, which she took with her in 1540 when she was forced from the convent during reformation. Height 89.5 cm, width 220 cm, depth

75.5 cm. It has the Luneburger construction type which shown by its size, the side of the chest and the lid. This chest is also interesting because it was painted (remnants can be seen on the front) with heraldic symbols in gold. The lid of the chest is interesting as well because of the 'four-pass' decoration.

Truhe TR-NR 207 (ISN Ba 89). A Celler type chest dated

1294. Made of oak, height 92.5 cm, width 112.5 cm, depth 78.5 cm. The lower part

of the chest is bleached due to the dampness of the floor.

On the right inner side is a small side

chest. The lower legs are decorated with a simple circular chip carving.

Truhe TR-NR 207 (ISN Ba 89). A Celler type chest dated

1294. Made of oak, height 92.5 cm, width 112.5 cm, depth 78.5 cm. The lower part

of the chest is bleached due to the dampness of the floor.

On the right inner side is a small side

chest. The lower legs are decorated with a simple circular chip carving.

Truhe TR-NR 209 (ISN Ba 90). Oak chest of the Celler type dated

around 1300. Height 89 cm, width 107 cm, and depth 72 cm. Decorated with

nails and zigzag carving at the feet.

The left innerside shows a small side chest (see below right). The lid of this

side chest can be used to hold the large lid open. Inside also the

remains of the bar lock can be seen (below left).

Not all chests in Kloster Isenhagen are hutch type chests. TR-NR 111 (ISN Ba 88) is a nailed slab-ended chest dated around 1400 and made from pine wood. Height 74.5 cm, width 151 cm, depth 61 cm. The bottom is joined with a groove and tongue to the sides, but nailed at the long side. The lock is asymmetrically positioned. It is likely that 13 cm of the chest is missing and has been sawn of.