My inspiration for the construction of the sella curulis came from the two medieval folding chairs on display in the Museum fur angewandte Kunst (MAK) in Vienna, Austria. Both are elaborately carved and brightly painted, as usual for this type of chair. The oldest is most widely known and shown in images. The other one is not. Unfortunately, you are not allowed to take photo's in the museum (in 2006), but they were so kind to mail me some photos they had of the chairs (in their glass show-case).

The oldest chair dates from the early 13th century and is made from pear wood. It originates from the Benedictine cloister Admont near Salzburg, Austria. The heads of the folding chair are carved as lions, while the feet are carved as dragons. The lions are the symbol of Christ, while the dragons symbolise the devil, showing the victory over evil.

The outer sides are decorated with are carved with rosettes, twines and shoots of plants, which are painted in red, green, white, yellow and blue. One of the lower rails has been replaced in the second half of the 15th century, and is decorated with the arms of the Admont stift and that of the abbot Johann Trautmannsdorf (1466-1481). The other medallions depict an eagle, griffin, lion and pelican. More recent replacements are the leather of the seat, the other - undecorated - lower rail and one of the x rails (seen on the photo by the uncarved and undecorated head).

The inner side of the chair is undecorated and uncarved, except for the heads and feet. Part of the wood at the centre of the x is removed to allow the chair to be folded and to have all parts of the x at the same level. An iron pin connects the both pieces of the x. The leather seating is folded over the upper rails and nailed to the underside of the wooden rail.

Images always show the Admont folding chair on this side, with the original complete x and the decorated rail with the medallions. Note that the lower jaw of the left lion is missing. Sizes of the chair are: 61 cm height, 64 cm width and 41.5 cm depth. Image from the book Mobel Europas I by Franz Windisch-Graetz.

Here you can see the other lower, undecorated replacement rail. Photo by the MAK, Vienna, Austria

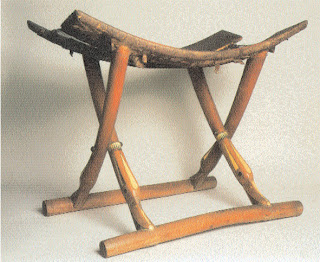

The second folding chair in the MAK also originates from the Admont cloister and dates from the 15th century. It is made from maple and painted in red with the chamfered sides in green. The chair is more crudely decorated. The centre of the X has carved and gilded rosettes on both sides. The heads of the chair are carved dog heads, with remains of gilding. The chairs' feet are dogs claws of which one is undamaged.

The sizes of the 15th century Admont chair are height 55 cm, width 63 cm and depth 43 cm. Photo by the MAK, Vienna, Austria.

Detail of the carved dog head of the 15th century Admont folding chair. The eye is painted white and the pupil black. Images from the book Mobel Europas I.

When I started drawing the construction plan I noticed that in 14th century miniatures the sella curulis hardly showed the lower rails connecting the two crosses. Some miniatures just show a frontal view of the sella curulis, but others seemingly have had loose feet. Could it be that the connecting beam was at a different place, for instance at the cross-section? Indeed, one medieval miniature shows a sella curulis with a rail at the x-section. I then changed my plan. Having the connecting rails at the a cross-section is more of a challenge, and I could always revert to having the rails like in the Admont chair.

A gilded sella curulis with lions heads and feet. 'Solomon judges among three brothers'

from a 'Bible historiale' of a Paris workshop around 1355. British Library, London, UK. Royal ms 19 D ii, fol. 273.

Solomon is seated on a 'gilded' sella curulis with lions heads. Solomon teaches the young Rehoboam

from a 'Bible historiale' of a Paris workshop around 1358. British Library, London, UK. Royal ms 17 E vii, fol. 1.

Two gilded 'sella curulis' for a King Solomon. The heads are either dogs or lions. 'The true brother refuses to shoot at his fathers corpse' and 'Solomon discovers the true mother' from the 'Bible historiale' made in a Paris workshop around 1369. Deutsche Staatsbibl., Berlin, Germany. ms. Philipps 1906, fol. 255.

'The King' seated on a elaborately carved sella curulis.The chairs' legs are 'hairy' and the complete chair is gilded. There are no rails between the lower legs of the chair. Miniature from the manuscript 'Polycratique' by John of Salisbury from a Paris workshop around 1373. Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris, France. ms. fr. 24287, fol. 12.

A gilded bishops sella curulis with dog heads. Miniature of the 'Sacrament of Confirmation' dating from 1390 from a Paris workshop. Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris. Tres Belles Heures de Notre Dame, ms. n.a. lat. 3093, p.169.

A gilded sella curulis with the connecting rails at the x-point. The top of the chair are carved dog heads. The chair itself is set on a dais, covered with cloth. The seat is folded over the the rails, and looks as if it is made of three pieces stitched together. Manuscript made in Paris in 1362. The Dauphin questions the antique astrologers. Neuf anciens juges d'astrologie. KBR, Brussels, Belgium, ms.10319, fol. 3.

A sella curulis from a miniature 'The knight before the royal council' dating from 1392-1393.

This folding chair clearly shows the connecting rails near the feet.

The chair's heads are concealed, but the feet of the chair look like simple feet. The chair is painted in bright red.

From the manuscript 'Pelerinage de vie humaine' by Guillaume de Digulleville.

Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Paris, France, ms. fr. 823, fol. 152.

The construction plan above still shows the sella curulis with the lower rails in place. I have a wooden pin locked inside the cross-section as the turning point (the black rectangles in the top and side view), instead of an iron pin through the wood. This will be changed for a turned wooden rail at the cross-section. The chair will be carved, except for the inside. The intention is to have the circles (frontal view) decorated with carved rosettes.

The next post on the sella curulis will continue with the preparation and sawing of the wood. Finally, this post concludes with the remains of an elaborately carved boxwood folding chair dating from the 13th? century in the Cathedral of Roda de Isabena in Spain. The folding chair is associated with San Ramon (sandals and handkerchiefs of the saint are shown as well), and has a curious story of theft, destruction and recovery.

The recovered remains of the chair now attached to a transparent plastic folding chair.

This is how the chair looked before the theft and destruction.

Image from Historia del Mueble by Luis Feduchi.

.

.